eLearning is Dead (Or is it?)

By Marcus Thraen and Doug Wintermute.

Sadly, it’s true; eLearning is dead…or, at least, the early, far-fetched dream of eLearning is.

While the term eLearning (coined by Jay Cross (Cross 109)) only surfaced in 1998, the concepts, the hopes, and (unfortunately) the realities of “eLearning” were witnessed long before the internet in other forms of distance learning.

Over the past 200 years or so, we have been teased with countless promises of futuristic distance learning and learning theories that seem to pop up with each new medium. At first, almost every technology is promised to change the standard method of instruction, reinvent the way students learn, and even enhance their cognitive responses.

In the end, however, while many new mediums have tested the educational waters—some performing comparable to face-to-face instruction, others failing miserably—none ever made significant changes to the institution of education.

Simply put, eLearning is learning through electronic multimedia, which can enhance learning and student outcomes by capitalizing on a superior method of delivery and implementing various learning theories.

Today, we think of eLearning as “learning online”. Before online was online, though, there was computer-based learning, television and radio learning, mail correspondence and more. These are all categorized under the umbrella term “distance learning”. At their core, every form of distance learning is the same: each is a method of learning that integrates advanced learning theories with new technology.

So, why hasn’t education changed? Or…has it?

History has been kind enough to lay out a set of trends that follow the adoption of new educational technologies; now, we can learn from it.

A Brief History of Distance Learning

The earliest documented example of distance learning comes from a shorthand teacher’s advertisement offering weekly lessons by post in the Boston Gazette in 1728.

Over 100 years later, in 1840, Sir Isaac Pitman started teaching shorthand on postcards, mailing assignments back and forth between himself and his students throughout Great Britain.

Early initiatives like these were designed to provide convenient study for those who would not have the time, money, or opportunity to partake in more traditional learning environments. But everything we thought we knew about education was about to change, thanks to the invention of the radio!

…Or, at least, that’s what we thought.

The radio brought with it a hope that education would be broadcasted to everyone, everywhere. In the 1920s, almost 200 American radio stations broadcasted distance education to the general public (Bower 7). It never did live up to its potential, though.

According to Douglas B. Craig, rising broadcast costs, diminishing audience interests, unfavorable frequencies, and poor time slots all led to the steady decline of radio education. Additionally, there was a concern that the effectiveness of lectures were lost in translation over the new medium.

While there were some programs that found long-running success with more conversational models (like the University of Chicago Round Table), radio’s educational format was too far gone by that point–especially when compared to the excitement and promise aroused by a new, better medium that was going to change education forever: This time for real (Smithsonianmag.com).

Enter: television!

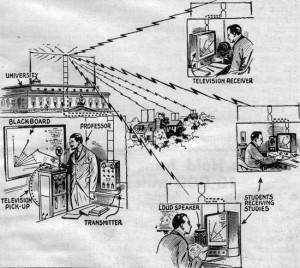

The early enthusiasm for television education was quick to multiply but slow to develop (Adams 197).

In 1933, the University of Iowa became the first educational institution to broadcast educational content on the TV, though true educational television did not become prominent until the 50s–specifically, when Western Reserve University first offered television courses (Smithsonianmag.com).

For classrooms, TVs were expensive; for the home, TV education required both the student and TV to be available at a specific time. Yet, the hope that the technology would offer a superior education far outweighed the challenges–at least, it was, until 1956, when Gayle Childs undertook one of the first ever educational media studies. His conclusion? That television was not a method of instruction but merely an instrument of its delivery. This was ultimately damning for educational TV (Almeda 68). While we still have educational television shows, the visions of using TV to deliver enhanced education were all but erased after the publication of that research.

It wasn’t until 1984, when computer-based training (CBT) was developed, that the next “big thing” in distance education came about–officially realizing the first phase of eLearning!

Computer-based training had effectively cut out the classrooms and the teachers, and the world was captivated. Requiring only a computer and a CD-ROM, students everywhere could learn whatever they wanted from home.

And yet, it still stumbled out of the gate.

Students weren’t engaging with the education the way it had been hoped they would. The idea of learning was so intertwined with the physical classroom setting that it was difficult to separate the two, and enrollments suffered (Cross 105).

In 1999, when eLearning systems and technologies first hit the ground, the previous hope that was once put on computer-based training was instead moved to the World Wide Web. This new system of education, once again, felt like it would change the world! Sales were enormous and excitement was palpable.

…But, soon after, the bleak reality set in: eLearning felt an awful lot like regular learning (Cross 107).

Hyping eLearning (A Case of Déjà vu)

The promise of technology has long proven to be a mirage for the educational world, both alluring and deceiving.

Despite the enthusiasm for early radio and television education, the reality that unfolded was not nearly as exciting. And even though the luxury of completing an education at home was well received, the early buzz for radio and TV education was slow to translate–and the research was anything but supportive!

With each new technology, the enthusiasm for new knowledge-delivery methods and easier learning run rampant. Each time, new and complicated learning theories are created, hypothesizing how the technology will enhance learning. Radio, television, satellites, the computer, and the Internet have all, in one way or another, been teased as the technology that will finally allow us to take that next step–but it was never to be.

At least, not yet.

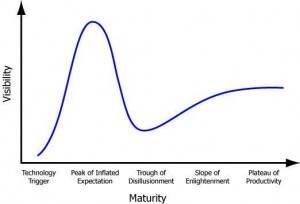

Though it has no objective grounding (and is better described as a curve than a cycle), the Hype Cycle produced by the Gartner Group is a helpful visualization of how a technology’s potential is dramatically hyped at first, then downplayed, and then gradually realized.

Why this happens is more difficult to explain, but it likely has more to do with marketing and consumer consumption tendencies than the technology itself. Regardless of the cause, the fact that the effect tends to replicate itself historically with each new technology is interesting in and of itself!

The Hype Cycle via the Gartner Group

However, it isn’t the marketers who are solely to blame for predicting an educational renaissance with each new medium; the fault also lies with the policy makers.

Concurrent with the birth of eLearning, there was a change in the language of the learning process, transitioning it back to an archaic “delivery” model, as opposed to a constructive partnership between teacher and student.

Like radio, TV, and computer-based learning before it, eLearning was pegged as the savior, the medium that was to raise the efficiency of the educational system as a whole (Mayes 4). How could it ever succeed with such inflated expectations?

The Underwhelming Realities of eLearning

When computers entered the educational fold, experts from all over the world thought up new and complicated eLearning theories and principles that explained the best ways of learning via computer.

As computer technology advanced in leaps and bounds, educational best-practices struggled to keep up. Computer-based learning theories were adopted by the Internet and became eLearning theories–but are they really the same media?

During this period, two debates raged on. One asked, “Which learning principle is best?” There was never any consensus. In fact, the technology was moving so fast that it was surpassing both the theories and the evaluations of those theories (Wisher & Champagne, 2000).

The other debate was called the Media Effects Debate, which asked simply, “Does educational technology even matter?”

One of the major players in the Media Effects Debate was Richard E. Clark. Following in the footsteps of Childs before him, Clark makes the claim that various forms of media “are mere vehicles that deliver instruction but do not influence student achievement any more than the truck that delivers our groceries causes changes in our nutrition. Basically, the choice of vehicle might influence the cost or extent of distributing instruction, but only the content of the vehicle can influence achievement” (445).

While it may still be unclear who is right (or even why), the reality is that eLearning, like all learning technologies that have preceded it, never lived up to the hype.

In 2003, only four years after the initial surge of anticipation for eLearning, it seemed to be sputtering. Conferences were stagnant–their attendances down 50%–and eLearning companies were downsizing. Revenue was lower than ever, and the buzz had all but disappeared (Cross 109).

So, what happened? Well, it appeared that eLearning had simply settled into its actual potential.

Like the Hype Cycle demonstrates, the hype for eLearning had already risen and fallen; now, it was time for reality.

But eLearning hadn’t actually gone anywhere; in fact, it was actually thriving! It just never dramatically changed the educational world in the quite way people had hoped it would.

Where Do We Go From Here: Online Video Learning

Today, eLearning is still in a state of confusion. Despite eLearning theories being largely unproven (and their numbers expanding yearly), many organizations still employ them in their eLearning programs.

At this very moment, eLearning is scaring off organizations with complicated course setups, high-tech authoring tools, intricate learning assessments, and convoluted designs–all without documentable confirmation that any of this even works!

So, what do we know about eLearning?

Well, we know it provides a more interactive, more personalized, and more convenient delivery method than traditional education. However, it requires the same great content, effective leadership, and strong instruction that in-person classrooms require.

Educational technology is useful for enhancing administrative efficiencies, like student tracking and assessment data, and it provides for increased, more flexible, and better accessible professional development (McMillan et al 22).

We know that technology, at this moment in time, is a helpful aid in the educational world–it just isn’t a new world altogether. It really doesn’t have to get any more complicated than that!

So, before we lament the death of eLearning, let’s look at the good news.

Online video learning is alive and well. Instead of reinventing the wheel, we can use the content and the technology that we already have. Organizations can record their lessons, put them to use, and even monetize them.

Anyone with a smartphone has a decent camera can easily record educational content, whether it’s a lecture, a conference session, or anything else. You can then take that content and publish it on a website or learning management system (LMS).

Simply take your content (the video lectures, lessons, whatever) and package it by presenting it in an easy-to use, recognizable format for learners. That’s all there is to it! Proven simplicity.

So perhaps, in the end, eLearning isn’t dead at all–it was just misunderstood from the start.

It may be that, in our drive to streamline and make effortless the educational process, we unfairly projected and prophesied outcomes for eLearning that were unattainable.

There needs to a conscious effort by everyone involved to set the record straight: eLearning is still just learning–and that’s not a bad thing!

With online video learning, we have a modern way of reaching wider audiences and improving access, availability, and timing. It allows you to give learners a solid education–nothing more, nothing less.